Source

“As soon as the Bolsheviks break away from the masses and lose contact with them, they should cover themselves with bureaucratic rust, so that they lose all strength and become an empty shell,” Stalin warned

Today, even the vicious enemies of Soviet power do not deny the rapid economic development of the Soviet country in the pre-war years. True, the slanderers are trying to denigrate the labor feat of the Soviet people, keeping silent about the popular enthusiasm of the builders of the first Stalinist five-year plans and assuring that the Soviet economy was created only with the help of gross violence. However, it is impossible to deny the existence of factories, factories, entire industries, large cities created during the Stalinist five-year plans that still exist today.

But the anti-Soviets do not want to hear when evidence is presented about the democratic character of the Soviet political system. Having distorted the concept of "democracy", which from time immemorial meant "rule of the people," the apologists of capitalism assert that the bourgeois system, which consolidates the omnipotence of the exploiting minority, is the pinnacle of democracy. Since the victory of capitalism in Russia put an end to true democracy and no traces of the former democracy remain, it is easier for slanderers to prove, especially to the generation born after 1991, that the USSR was a kingdom of tyranny and terror.

The slanderers who control the mass consciousness of modern Russia are especially hated by the evidence of Stalin's role in the implementation of democratic political transformations. They hysterically declare that Stalin and democracy are incompatible concepts. Perhaps for this reason, citing indisputable archival documents about the political reforms of the 30s, carried out on the initiative of I.V. Stalin, the historian Yuri Zhukov called his book "Another Stalin". The idea of Stalin as a fighter for the democratization of Soviet society contradicts the ideas embedded in the mass consciousness. Indeed, in accordance with them, the Soviet system, created on the basis of communist doctrine, is the embodiment of tyranny.

Meanwhile, Stalin's struggle for democratic political reforms naturally and logically followed from his Marxist-Leninist ideas about the development of democracy as socialism was being built, as well as about the correspondence of the political institutions of society to the nature of its economic relations. In the mid-1930s, Stalin raised the question of the need for democratic changes in the country's constitutional structure, which would reflect the grandiose changes that had taken place in the economy and social life of Soviet society.

How the 1936 Constitution was created

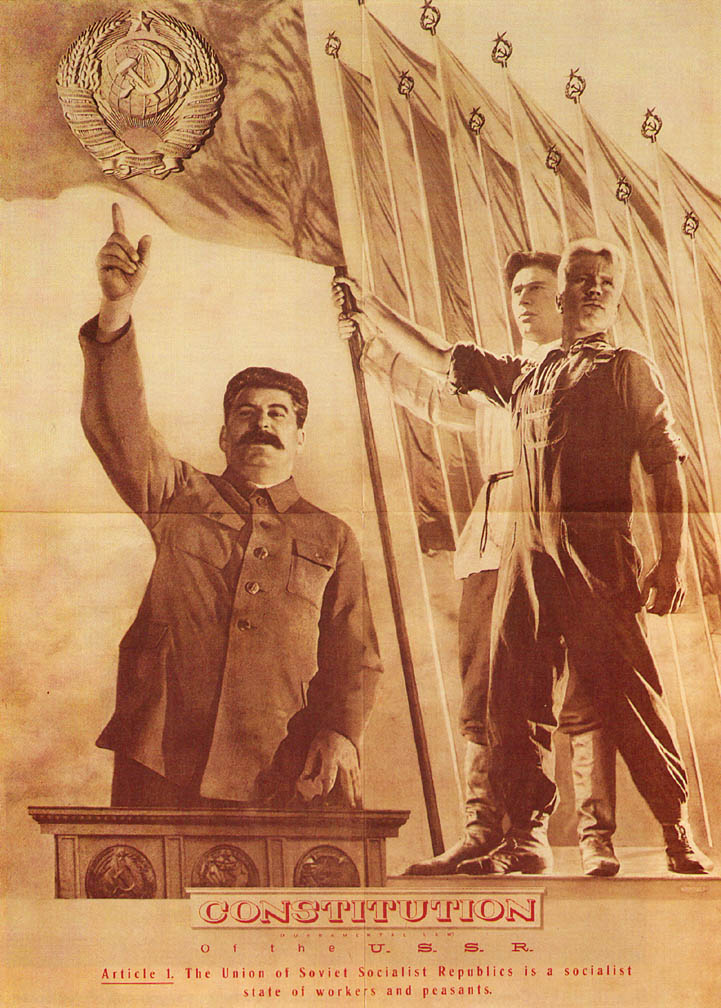

The current authorities and the bourgeois media try not to remember the Stalinist Constitution. If it is mentioned, it is portrayed as a "smokescreen" designed to hide the mass repressions prepared in advance. So, in his book about Stalin, E. Radzinsky wrote: "Before the New Year, Stalin arranged a holiday for the people: he gave him the Constitution, written by poor Bukharin." This short phrase contains several factual errors. First, the Constitution was adopted not “just before the New Year,” but on December 5, 1936. Secondly, the new Constitution was not "given" from above. Its adoption was preceded by many months of nationwide discussions of the draft constitution. Thirdly, Bukharin was not the author of the Constitution, but only headed one of the subcommissions on its preparation.

The myth of Bukharin as the creator of the Soviet Constitution is constantly repeated today on all television channels. The host of the Top Secret program Svyatoslav Kucher called Bukharin the "Creator of the Constitution". Even during one of the popular programs "Clever and Clever", its participants were taught that the Constitution of 1936 was written by Bukharin.

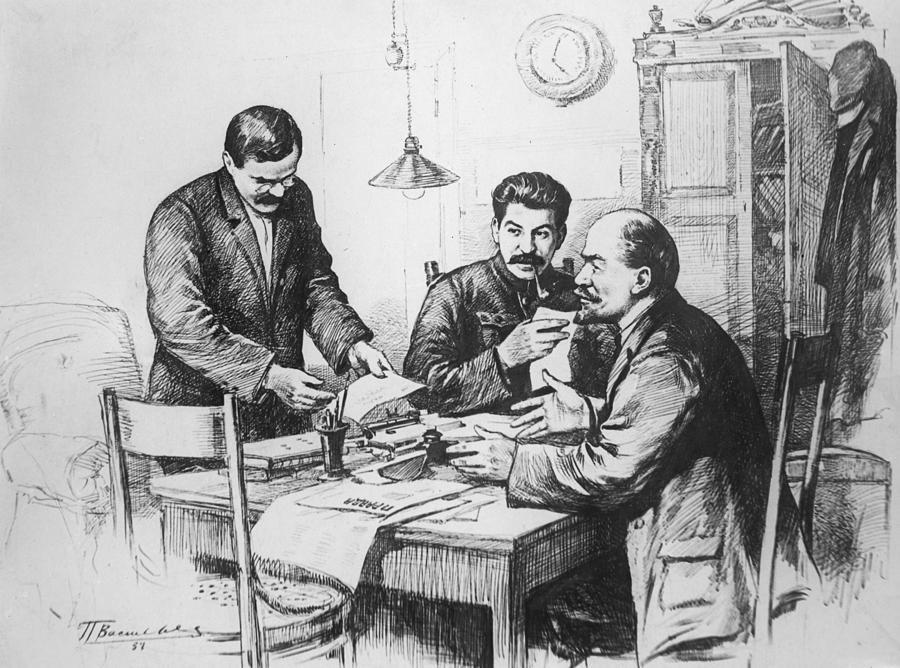

In fact, the Constitution was not the product of one man's efforts. The development of individual sections of the Basic Law of the USSR was carried out by 12 subcommissions, and their proposals were summarized by the editorial commission, which consisted of twelve chairmen of the subcommissions. At the same time, the facts indicate that the initiative to revise the 1924 constitution, and then to create a new constitution, came from I.V. Stalin. At a meeting of the Politburo on May 10, 1934, at the suggestion of Stalin, a decision was made to amend the country's Constitution. Stalin headed the entire editorial commission, as well as the subcommittee on general issues.

In a conversation with the author of this article, the former chairman of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR A.I. Lukyanov told how in 1962, fulfilling the instructions of the then leadership of the country, he had the opportunity for several months to study archival materials concerning Stalin's work on the draft Constitution. A detailed note on this issue of several hundred pages was written by Lukyanov and presented by him to the Presidium of the Central Committee.

From the materials with which he got acquainted, it followed that in the course of their work, the members of the editorial commission brought Stalin various versions of the so-called rough draft of the draft constitution. After that, Stalin re-ruled her articles over and over again.

A.I. Lukyanov emphasized: “Joseph Vissarionovich understood very well that the essence of socialist democracy is to ensure real human rights in society. And when N. Bukharin, who headed the legal subcommittee, proposed to preface the text of the constitution with the "Declaration of the Rights and Duties of Citizens of the USSR," Stalin did not agree with this and insisted that the rights of a Soviet citizen be enshrined directly in the articles of the constitution. Moreover, they were not just proclaimed, but guaranteed in the most detailed way. So for the first time in world practice, the Basic Law of the country introduced the rights to work, rest, free education and health care, social security in old age and in case of illness. "

Anatoly Ivanovich Lukyanov further noted: “It was amazing how meticulously Stalin worked on the wording of each article of the constitution. He revised them many times before bringing the final text up for discussion. So the 126th article, which deals with the right of citizens to unite, Stalin wrote himself and rewrote and revised several times. " In total, Stalin personally wrote eleven of the most significant articles of the Basic Law of the USSR.

According to Lukyanov, Stalin, trying to develop the democratic foundations of the Soviet system, carefully looked at the historical experience of world parliamentarism. A record of his speech has been preserved in the archives: “There will be no congresses ... The Presidium is the interpreter of laws. The legislator is a session (parliament) ... The executive committee is not good, there are no more congresses. Soviet of Working People's Deputies. Two chambers. Supreme Legislative Assembly ". By agreement with I.V. Stalin V.M. Molotov, in his report at the VII Congress (February 1935), spoke of a gradual movement "towards a kind of Soviet parliaments in the republics and towards an all-Union parliament."

At the same time, Lukyanov emphasized, it should be borne in mind that Stalin did not mechanically copy the models of parliamentary practice, but took into account the experience of the Soviets accumulated over two decades. He personally included in the text of the Constitution the 2nd and 3rd articles, stating that the political basis of the USSR is made up of the Soviets of Working People's Deputies, which grew and became stronger as a result of the overthrow of the power of the landowners and capitalists and the conquest of the dictatorship of the proletariat, and that all power in the USSR belongs to the working people of the city and villages, represented by the Soviets, who do not know the division of powers and have the right to consider any issues of national and local importance.

Another important principle was the supremacy of the Soviets over all accountable state bodies based on mass representation (more than 2 million deputies) and the right of the Soviets to decide, directly or through their subordinate bodies, all issues of state, economic and socio-cultural development.

By March 1936, work on the text was largely completed. In April, the "Rough Draft" of the Constitution of the USSR was developed. It, in turn, was revised into the "Preliminary draft of the Constitution of the USSR", which on May 15, 1936 was adopted by the constitutional commission. Then the project was approved by the June (1936) plenum of the Central Committee of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks), and on June 11 - by the Presidium of the USSR Central Executive Committee, which ordered its publication.

The draft Constitution of the USSR was published in all newspapers of the country, broadcast on the radio, published in separate brochures in one hundred languages of the peoples of the USSR with a circulation of over 70 million copies. The scope of the nationwide discussion of the draft is evidenced by the following data: it was discussed at 450 thousand meetings and 160 thousand plenums of the Soviets and their executive committees, meetings of sections and deputy groups; over 50 million people (55% of the country's adult population) took part in these meetings and sessions; during the discussion, about 2 million amendments, additions and proposals to the project were made. The latter circumstance testifies to the fact that the discussion of the draft was not formal.

(Continued in the comments)