marxism

For the study of Marxism, and all the tendencies that fall beneath it.

Read Lenin.

Resources below are from r/communism101. Post suggestions for better resources and we'll update them.

Study Guides

- Basic Marxism-Leninism Study Plan

- Debunking Anti-Communism Masterpost

- Beginner's Guide to Marxism (marxists.org)

- A Reading Guide (marx2mao.com) (mirror)

- Topical Study Guide (marxistleninist.wordpress.com)

Explanations

- Kapitalism 101 on political economy

- Marxist Philosophy understanding DiaMat

- Reading Marx's Capital with David Harvey

Libraries

- Marxists.org largest Marxist library

- Red Stars Publishers Library specialized on Marxist-Leninist literature. Book titles are links to free PDF copies

- Marx2Mao.com another popular library (mirror)

- BannedThought.net collection of revolutionary publications

- The Collected Works of Marx and Engels torrentable file of all known writings of Marx and Engels

- The Prolewiki library a collection of revolutionary publications

- Comrades Library has a small but growing collection of rare sovietology books

Bookstores

Book PDFs

Painting: Stalin as a Jew, 1986–1987 - Alexander Kosolapov

Was Stalin antisemitic? The answer may seem obvious, given the Soviet leader’s role in directing the campaign against the so-called “Doctors’ Plot.” Between 1952 and 1953, Stalin unleashed a flurry of repression in which a group of prominent Moscow doctors—most of them Jewish—were falsely accused of conspiring to assassinate senior Soviet officials through intentional medical malpractice.1 This case was part of a larger repressive campaign that targeted intellectuals and professionals accused of harbouring foreign loyalties, particularly linked to Zionism and the newly established state of Israel in Palestine. Many citizens were dismissed from their jobs, imprisoned, and tortured into false confessions after being accused of “cosmopolitanism.”2 After Stalin’s death in March 1953, the charges were declared baseless, and the surviving doctors were released.

Stalin’s orchestration of this campaign is usually assumed to have been motivated by antisemitic tendencies. While at first glance this appears to be a clear case of bigotry against Jews, this view has been challenged by a number of historians who emphasize instead Stalin’s primarily political motivations. For instance, Geoffrey Roberts, a leading specialist on Stalin, writes that Stalin was not so much “anti-Semitic as he was politically hostile to Zionism and Jewish nationalism.”3 This view is echoed by one of Stalin’s biographers, Christopher Read, who notes that newly available evidence “should make observers hesitate to argue, as is widely done, that a general anti-Semitic campaign was under way [under Stalin].”4 The scholars Yu Xiao and Ji Zeng write that Stalin’s decision-making during this period can be better explained by his “paranoiac political worldview than by antisemitic tendencies.”5 Additionally, the British historian Robert Service describes these events as emerging from “realpolitik rather than visceral prejudice.”6

The fundamentally political nature of Stalin’s anti-Zionist campaign is why, Christopher Read observes, non-Jews also came to be targeted while, at the same time, many Jews remained untouched. Indeed, there were prominent Soviet Jews who enthusiastically participated in the campaign against Zionism, such as “the philosopher and member of the Academy of Sciences, Mark Mitin; the journalist, David Zaslavsky, and the orientalist, V. Lutsky.”7 Benjamin Pinkus, a historian of Soviet Jewry, writes that “the chief victims” of the anti-cosmopolitan campaign were “two non-jews” and that there no “explicit or implicit anti-Jewish tone in the campaign,” [emphasis mine] a notion that is consistent with Stalin’s own worldview, as historian and anti-Soviet dissident Zhores Medvedev writes:8

Stalin was neither an anti-Semite nor a Judeophobe. Judeophobia can be understood as an intense hatred toward any member of the Jewish people — something Stalin did not exhibit. Nowhere in his official speeches or archival documents is there a statement that can be fairly described as anti-Semitic.9

If, in the words of Geoffrey Roberts, Stalin “was not anti-Semitic in any meaningful sense,” what explains the cause of these events?10 This episode of repression can be better explained by taking a closer look at Stalin’s almost obsessive suspicion of “bourgeois nationalism.”

Prior to this, Stalin carried out a number of repressions against perceived anti-Soviet nationalisms, and while the anti-cosmopolitan campaign had distinctive elements given its Cold War context, it generally adhered to the same Stalinist logic, violent repression against any perceived support of bourgeois nationalism. Kazakh, Armenian, Latvian, Ukrainian, Estonian, and other groups, at various times faced accusations of anti-Soviet bourgeois nationalism. The term specifically denoted those nationalist tendencies that were perceived as attempting to restore bourgeois class dominance and capitalist exploitation. According to Stalin:

the bourgeoisie of the oppressed nation, repressed on every hand, is naturally stirred into movement. It appeals to its "native folk" and begins to shout about the "fatherland,'; claiming that its own cause is the cause of the nation as a whole. It recruits itself an army from among its "countrymen" in the interests of ... the "fatherland." Nor do the "folk" always remain unresponsive to its appeals; they rally around its banner: the repression from above affects them too and provokes their discontent.”11

Any ties to a pre-Soviet or non-Soviet national identity were seen as a liability exploitable by foreign intervention; thus, national expression was to be expressed within the acceptable parameters of Soviet identity. Notably, this did not mean Russification, but that minority national expression had to be compatible with the overarching ideals and values of a universal socialist identity as understood by the Soviet state.12 One was to be a Soviet Kazakh or Soviet Armenian, for instance.

Terry Martin writes that the USSR took deliberate efforts to promote “distinctive national identities,” efforts which “actually intensified after December 1932,” during the Stalin era.13 For Stalin, the supranational multiethnic community of the “Friendship of Peoples” was a fundamental component of a universal Soviet identity. Martin observes that while the Soviets eventually accorded Russia a symbolic leading role in this multinational system, state support for non-Russian culture, historical education, and language instruction within each socialist republic remained strong, writing that “with respect to policy toward most non-Russians, then, the affirmative action empire continued with limited corrections throughout Stalin's rule.” 14

There was no Stalinist attempt to replace minority identity with a Russian one, contrary to popular belief. Elissa Bemporad’s excellent case study on Jewish community in Minsk describes how early Soviet equity policies fostered the formation of a distinct Soviet-Jewish identity in which Jewish and Yiddish culture were actively promoted and celebrated within the framework of socialist nationality policy.15 These policies stood in stark contrast to the popular attitudes towards Jews in European nations. Bemporad describes how “local Jews, acutely aware of the governmental and popular anti-Semitism faced by friends and relatives in Poland, still felt pride in their Soviet identity” despite living in a climate of repression during the height of Soviet terror in the 1930s.16 What has been perceived as state-endorsed antisemitism should be situated within the historical context of Stalin’s mounting hostility and paranoia toward Zionism, which took shape in the aftermath of the war.

While the USSR had a long-standing ideological opposition to Zionism, it initially supported the creation of the State of Israel in 1947–1948. This cynical maneuver marked a departure from the prior policy and was justified on strategic grounds: by backing the end of the British Mandate in Palestine and arming Jewish paramilitary groups through Czechoslovakia, the Soviet leadership aimed to weaken British influence in the Middle East and potentially bring a new socialist-leaning ally into the Soviet sphere. However, this hope quickly dissipated. The new Israeli state aligned itself with the United States, signalling to Soviet leaders that Zionism was more likely to serve as a vehicle for Western influence than socialist solidarity. Those who suffered the most from the Soviet reversal were the indigenous population of Palestine, who faced brutal atrocities and displacement, often at the barrels of Soviet-funded weapons.

Because of Israel’s favourable positioning towards the USSR’s enemies, domestic opposition to Jewish nationalism became a matter of paramount importance for Soviet leadership. Concerned about foreign influence and political loyalty within their borders, Stalin’s government took increasingly repressive measures to counter what it viewed as possible conduits of anti-Soviet bourgeois nationalism. Stalin’s anti-cosmopolitan campaign was aimed at rooting out individuals deemed insufficiently loyal to Soviet values and overly influenced by foreign ideas.17

The campaign promoted Soviet patriotism and cultural conformity while condemning so-called rootless intellectuals who were accused of undermining national unity and socialist patriotism. This insular worldview was a Cold War backlash against the perceived encroachment and intrigue of the capitalist world, signalling a new socialist defense of the motherland and its national character. Although “rootless cosmopolitanism” is often read retroactively as a coded antisemitic slur, in its original Soviet usage it functioned as a broader ideological critique rather than targeting Jews or Zionists specifically. The ideological basis of the term, argues Van Ree, fundamentally “rested on patriotic etatism and militant anti-capitalism” rather than traditional Russian antisemitism.18 It was primarily deployed to denounce individuals perceived as lacking loyalty to the Soviet state and espousing cultural servility to the capitalist West, and was used against many non-Jewish intellectuals and artists who engaged with Western ideas.19 Tellingly, Van Ree writes that Stalin conceptualized the Russian tsarist tradition as the main source of cosmopolitanism, a tradition which was virulently antisemitic itself and was often criticized on this basis by Stalin and the Soviets (in a speech Stalin had once remarked that “the Hitlerites suppress … the rights of nations as readily as the tsarist regime suppressed them, and that they organize mediæval Jewish pogroms as readily as the tsarist regime organized them.)20 21

The exceptional ferocity of Stalin’s anti-nationalist campaign against Zionism is tied to the heated Cold War tensions of the period. Stalin was alarmed by the enthusiastic response Soviet Jews gave to the establishment of Israel, particularly the outpouring of support following the visit of a Golda Meir envoy in 1948, which saw thousands of Soviet Jews publicly celebrate her arrival and express deep emotional attachment to the new Jewish state.22 Letters poured in from across the USSR proclaiming Israel as “our” country, a sentiment that deeply unsettled Stalin, who viewed such displays of transnational loyalty as absolutely antithetical to the kind of Soviet patriotism that was expected of all Soviet citizens.23

These factors primed Stalin’s cataclysmic response to all and any perceived Jewish nationalism, however tenuous.

Bourgeois Nationalism

There is a tendency to characterize the anti-Zionist campaign as a manifestation of classic Russian antisemitism, in continuity with tsarist pogroms and state-sanctioned violence against Jews. Van Ree points out that this seems intuitive, but there is no archival evidence that directly substantiates any connection.24 Rather, Stalinist anti-Zionism was part of a broader pattern of distinctly Soviet political repression, in which numerous groups had been targeted at different times under the charge of bourgeois nationalism.25 In one example, repression during the 1930s targeted a wide range of Ukrainian intellectuals and political figures accused of promoting Ukrainian nationalism.26 In one example, repression during the 1930s targeted a wide range of Ukrainian intellectuals and political figures accused of promoting Ukrainian nationalism.26 Among them were members of the so-called Executed Renaissance, a generation of writers, artists, and cultural leaders who were arrested, imprisoned, or executed. One major factor fueling these repressions was official suspicion of ideological links between Soviet Ukrainian writers and émigré nationalist figures abroad.

Notably, in the 1920s, the prominent Soviet Ukrainian writer Mykola Khvylovy engaged with the ideas of Dmytro Dontsov, a proponent of integral nationalism—a radical, fascist ideology. Although Khvylovy remained a committed communist, incorporating these ideas within his ideologically communist framework, he was drawn to Dontsov’s vision of cultural revival and national assertiveness, ideas that would influence the fascist Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists (OUN).27 For Soviet authorities, any flirtation with émigré ideologues like Dontsov was seen as a dangerous, potential threat.

We do not have the space to review every Stalinist repression of bourgeois nationalism, but there were many. Robert Service writes: “Stalin moved aggressively against every people in the USSR sharing nationhood with peoples of foreign states.”28 Similarly, Lindemann, a scholar of antisemitism, writes that Stalin’s “hatreds and suspicions knew no limits; even party members from his native Georgia were not exempt.”29 Indeed, Stalin grew concerned over Mingrelians—a Georgian ethnic subgroup—“dominating others in the political hierarchy” and forming ethnic patronage cliques.30 Stalin grew particularly wary of Lavrentiy Beria, a Mingrelian whose growing influence he perceived as the major beneficiary of these developments in Georgian politics, and hence a potential threat. What began as accusations of bribery and corruption soon morphed into paranoid allegations of involvement in a so-called “Mingrelian nationalist ring” and collaboration with Western imperialists.31

While there is little evidence that Stalin harbored explicit ethnic or racial hatreds, there is ample documentation of his deep suspicion toward political nationalism, which he viewed as a potential threat to Soviet unity and a possible conduit for foreign infiltration and collaboration. As a result, Stalin was acutely concerned with the “loyalty” of various nationalities and their susceptibility to international intrigue. A useful framework for understanding this mindset is what Terry Martin terms “Soviet xenophobia”—defined as “the exaggerated Soviet fear of foreign influence and foreign contamination.”32 Importantly, Martin clarifies: “I absolutely do not mean traditional Russian xenophobia. Soviet xenophobia was ideological, not ethnic. It was spurred by an ideological hatred and suspicion of foreign capitalist governments, not the national hatred of non-Russians.”33 This distinction becomes especially evident in cases such as NKVD Order No. 00593, which targeted an ethnic Russian diaspora group for their perceived transnational affiliations and threatening territorial proximities:

National Operation, initiated by NKVD Order n° 00593 on September 20, 1937 … targeted the so-called "Kharbintsy". These were former personnel (engineers, employees, railway workers) of the Chinese-Manchurian railway whose headquarters were based in Kharbin, in Manchuria. After the sale, by the Soviet government, of this railway to Japan in 1935, many returned to the Soviet Union. For Stalin and his team, although most of the Kharbintsy were ethnic Russians, their cross-border ties to the Kharbintsy remaining in China turned them into the functional equivalent of a diaspora nationality. And so, despite their "Russianness", they too became an "enemy group" targeted as part of the National Operations during the Great Terror34

This episode of repression exemplifies the distinctly ideological and political nature of these kinds of repressions, which were primarily concerned with security issues tied to primarily politico-territorial conceptions of identity rather than ethnic ones. Here, a Soviet state led by an ethnic Georgian was carrying acts of repression against a group of ethnic Russians. What made individual(s) vulnerable to Stalin’s ire was not a deep-seated prejudice based on racial doctrines or cultural stereotypes, but perceived ideological contamination of nationalities through territorial proximity, suspect geopolitical connections or international contact with hostile capitalist entities, which, nonetheless, invariably entailed forms of collective punishment. Stalin’s anti-Zionist campaign should be situated within this context.

To exceptionalize the Soviet repression of Jewish nationalism as an entirely unique and separate form of violence in comparison to other anti-nationalist campaigns is to risk retrofitting post-Holocaust frameworks onto a Stalinist logic of repression predicated on political and ideological motivations, rather than ethnic ones. Just as various other “nationalist deviations” were subjected to suspicion and repression due to their perceived geopolitical associations, so too was Jewish nationalism targeted in the context of growing Soviet hostility toward Zionism and the Western bloc. What also distinguishes Stalin’s anti-Zionism from traditional European antisemitism was Stalin self-professed strident opposition to antisemitism. Not only did Stalin not have any documented antisemitic remarks or directives, he condemned antisemitism in the harshest of terms:

in 1927 [Stalin] explicitly mentions that any traces of anti-Semitism, even among workers and in the party is an “evil” that “must be combated, comrades, with all ruthlessness.” And in 1931, in response to a question from the Jewish News Agency in the United States, he describes anti-Semitism as an “an extreme form of racial chauvinism” that is a convenient tool used by exploiters to divert workers from the struggle with capitalism. Communists, therefore, “cannot but be irreconcilable, sworn enemies of anti-semitism.” Indeed, in the U.S.S.R. “anti-semitism is punishable with the utmost severity of the law as a phenomenon deeply hostile to the Soviet system.” Active “anti-semites are liable to the death penalty”35

Some have interpreted Stalin’s public condemnation of antisemitism as a progressive facade, suggesting it served to obscure the more insidious motivations of an authoritarian regime.36 According to this view, Stalin’s egalitarian ideology functioned largely as window-dressing, designed to deflect attention from what they see as the regime’s “real” animating impulses. This interpretation rests on the assumption that Stalin was consistently operating in a cynical and calculated manner—an assumption that, like any historical claim, requires supporting evidence. In this case, that would mean demonstrating a clear discrepancy between Stalin’s private writings or internal government correspondence and his public pronouncements. As historian Zhores Medvedev has noted, no such evidence has been uncovered. Indeed, the WWII specialist, Mark Edele, also cautions against this assumption, writing that the Soviet critique of antisemitism “should be taken more seriously” and that it complicates this history more than scholars have traditionally been willing to admit.37

However this lack of direct evidence does not rule out the possibility of antisemitic motives. One could argue that Stalin still harboured deeply seated antisemitic views, shaped by pre-revolutionary cultural norms, which he never acknowledged, perhaps in order to preserve the coherence of his professed egalitarian and internationalist worldview. From this perspective, Stalin’s alleged hatred of Jews can be inferred not from professed attitudes or ideology evidenced in archival documents but from patterns of behaviour and the concrete effects of his policies on Soviet Jews.

Anti-Antisemitism

This interpretation is complicated by two key factors: first, as previously mentioned, the chief targets of the so-called antisemitic campaigns were not Jewish, and many prominent Jews remained untouched. As historian Albert Lindemann observes, Stalin’s personal relationships and political appointments challenge the notion that he harboured a hatred of Jews:

Not only did [Stalin] repeatedly speak out against anti-Semitism but both his son and daughter married Jews, and several of his closest and most devoted lieutenants from the late 1920s through the 1930s were of Jewish origin—for example, Lazar Moiseyevich Kaganovich, Maxim Litvinov, and the notorious head of the secret police, Genrikh Yagoda … The importance of men like Kaganovich, Litvinov, and Yagoda makes it hard to believe that Stalin harbored a categorical hatred of all Jews, as a race.38

While Stalin may not have been personally antisemitic, antisemitism nonetheless existed within Soviet society, which undoubtedly included officials and party functionaries. These views often persisted despite the formal anti-antisemitic laws and ideology of the regime. As Van Ree notes, Stalin was at times directly confronted with such behaviour and pushed back against it:

In 1947, [Stalin] told Romanian party leader Gheorghiu-Dej that it was unacceptable to remove his colleague Pauker from high positions in the party merely because she was Jewish…Stalin also rejected Suslov’s proposal according to which “nationality” might be used as the official reason for dismissal from one’s work place.39

Stalin reprimanded his Romanian counterpart with a striking comment: “[One] must remember that, if their party will be class-based, social, then it will grow; if it will be racial, then it will perish, for racism leads to fascism.”40 This brings us to the second major factor complicating any straightforward narrative of Soviet antisemitism. Stalin’s line of reasoning in this interaction echoed the USSR’s project of promoting social equity among minority groups, including Jews. One key example of this was the korenizatsiya (indigenization) policy of the 1920s, which actively supported minority languages and cultures as part of the larger socialist nation-building effort. For Soviet Jews, this included the establishment of Yiddish-language schools, theatres, publications, and the creation of the Yevsektsiya, the Jewish sections of the Communist Party. 41

Elements of the indigenization policies wound down by the mid-1930s, and some have interpreted this as evidence that Stalin’s regime took a full conservative turn, abandoning its commitment to minority equity and moving toward a form of traditional Russian chauvinism, with antisemitism never far beneath the surface. There is no denying the stark shift that occurred by the late 1940s and early 1950s amidst the anti-Zionist campaign, when the Soviet state shuttered many Jewish cultural institutions due to growing fears around their extensive ties to religious and cultural organizations abroad, especially those based in the United States, which were increasingly seen as potential sources of ideological contamination.

This view of a chauvinistic, Russifying USSR is complicated by the fact that pro-minority policies continued for Jews at the height of an allegedly antisemitic campaign. Following the USSR’s territorial expansion during and after the Second World War, the Soviet state reintroduced aggressive affirmative action–style measures in what scholars have termed a period of “neo-indigenization,” once again working to aggressively remove social barriers through employment equity and popular education.42 This revival sheds light on how the Soviet leadership understood its minority equity policies—not as a continuous process, but as a distinct initial stage in the development of nations. Importantly, this renewed indigenization extended to Jewish communities in the newly annexed territories. These initiatives reflected a genuine effort to integrate and empower minorities within the Soviet system, complicating claims that antisemitism was a defining or consistent feature of Stalinist policy.

As historian Diana Dumitru has shown in her study of Soviet Moldavia, Jewish representation in civil and cultural institutions remained significant after 1948 in this region, and in some cases, even grew, precisely during the period often cited as the onset of official Soviet antisemitism:

The Jewish presence in Soviet Moldavia’s leading cultural institutions was also significant throughout the entire period, even if it showed some fluctuation. In 1945, 33 percent of the membership of the MSSR’s Union of Writers were of Jewish origin, and by 1949 this proportion increased to 43 percent; although it decreased back to 33 percent by 1953. Jews were a significant group in the Union of Composers of the MSSR: in 1948 the Union’s 18 members included eight Jews. Even more surprising, if one takes into account the climax of anti-Jewish sentiments in Moscow in the early 1950s, the proportion of Jewish members in the Union of Composers in the MSSR had increased further by 1953.18 members included eight Jews. Even more surprising, if one takes into account the climax of anti-Jewish sentiments in Moscow in the early 1950s, the proportion of Jewish members in the Union of Composers in the MSSR had increased further by 1953.18 Among the members of the MSSR’s Union of Artists, Jews comprised 16.6 percent for three consecutive years (1944–1946); their share dropped to 10.6 percent in 1948, yet grew again to 14–15 percent in the following years, and jumped to 20 percent by 1953. [43]

Dumitru describes how the new Soviet culture in Moldavia was a stark contrast to the previous antisemitic government, encouraging “the professional advancement of ethnic Jews to positions of power and prestige previously unmatched in this region.”44 The rapid facilitation of Jews into positions of power and their overrepresentation in professional areas “relative to their share of the population” in the region was enabled by the USSR’s broad decrees against antisemitism and the inclusive nature of its social policy.45 Likewise, Smilovitsky’s text on Jewish life in Belarus describes how “Jews rose to form a significant and disproportionately-sized group in leading managerial positions in Belorussia’s economic, educational, scientific, and cultural institutions between 1945 and 1950.”46 These anti-antisemitism policies had significant implications during WWII, saving countless lives.

In Dumitru’s comparative study of civilians' attitudes and behaviour toward the Jewish population in Romania and the occupied Soviet Union, she demonstrates that even brief periods of Soviet control significantly transformed local attitudes by actively combating antisemitism through state-led campaigns, education, and the promotion of internationalist socialist ideology.47 In one informative example, Dumitru describes how the state used social satire and theatre as forms of popular education against antisemitism:

Satire and public shaming were then highly regarded in the Soviet Union as educational tools. In their spirit, mock trials of antisemites were staged for the public, boldly taking on the particular preconceptions of the era. An American journalist who visited Kiev in 1932 attended such a play, which featured a clerk named Raznochintseva, who was accused of saying, “the Jews have already forgotten what a pogrom is like, but soon there will be another war and we shall remind them what it means to capture Russia’s government, land, factories, and everything else.” Influenced by her ideas, a peasant begins to complain that the Soviet government is giving land, seed, and credit to Jews, while only taking from the Russian peasants. The trial associated antisemitism with counterrevolution and the bourgeoisie, as well as with ignorance:

Raznochintseva: Don’t you know that [the Jews] have always been after easy money?

Attorney for the Defense: How well do you know any Jews?

Raznochintseva: Personally I know very few of them. I always avoid them.

Prosecutor: Did you ever read any literature about Jews?

Raznochintseva: I was not interested enough.

The play suggested that such individuals could easily corrupt those who do not read the Soviet press; Raznochintseva and several other witnesses all confirmed that their own antisemitic ideas were not backed up by any empirical knowledge. Even Raznochintseva’s boss, a Jew named Kantorovich, ends up on trial, for hearing antisemitic statements by his workers but doing nothing to stop them. In the end Raznochintseva is fired from her job and sentenced to two years for the “counterrevolutionary activity of inciting antisemitism.48

These policies were historically unprecedented both within the region and in the broader context of wartime Europe, fostering greater awareness among local populations of the dangers posed by Nazi racial doctrines. As a result, Transnistrian Moldova, under Soviet rule, witnessed far less collaboration than did Bessarabian Moldova, under Romanian rule.49 Dumitru’s findings highlight how the Soviet state’s ideological commitment to combating ethnic hatred and fascism shaped a material difference on the ground and undermine any straightforward characterization of the Stalinist state as inherently antisemitic. The apparent paradox between what some scholars have described as Stalinist antisemitism and the simultaneous promotion of Soviet-Jewish identity and anti-antisemitism was not truly a paradox at all. For the Soviets, it reflected two distinct but non-contradictory processes: the promotion of multicultural equity inclusive of Jews, alongside the repression of Zionism that, like all forms of bourgeois nationalism, was viewed as a threat to the Soviet state.

Indeed, Christopher Read, drawing on Medvedev’s research, writes that Stalin died just before the publication of a letter he had approved, written by Soviet Jews, which outlined the difference between Soviet Jews and cosmopolitans—likely as a means of correcting those on the ground who, contrary to Stalin’s intentions, interpreted the campaign as an antisemitic assault on all Soviet Jews.50 Read notes that Stalin sought to terminate the campaign at the end of his life but died before giving final approval, contradicting the common assumption that Stalin would have expanded his suppression of Jewish institutions had he not died when he did.

~~(first of all shush I know time zones make this seem funky)~~

Eighty years ago to this day, the People's flag was staked into the heart of most grievous reaction and the world celebrated victory over German fascism.

Eighty years later, we stand on the shoulders of those heroes. We stand in the world of their victory, as dark as it may be yet in contrast of what could have been, it is a world in which we can and must fight for a better tomorrow.

Let us not just spend the day honoring the sacrifice of the millions of men and women who have passed on the torch of humanity through nostalgic remembrance, but take onto us the legacy of their work to build the foundations of a better world and continue in their place so when the time comes for us to pass on the torch of humanity to the new generation we can say that out of the ruins of the old barbarism we have delivered to them a better future of peace and freedom and continue the great work towards the emancipation of the human race.

Forwards ever, backwards never.

I chose social (service) workers, because Social Worker is a protected title in many states in the US but there are many people who do not have their degree/licensure who engage in the same if not similar work so I wanted to capture that.

Gonna preface my ideas with the fact that I have a basic understanding of the classes so I could be off base and would love feedback/corrections if I'm not applying the terms correctly.

I think the kneejerk reaction from people when they hear that someone works in social services would be that they are petty bourgeois, but I believe that because the field is so broad, and there is so much overlap in work that it is both petty and proletarian. For example, licensed Social Workers can engage in private or group practice where they work for themselves. At the same time, they have the option of working in the public/private/nonprofit sector if they would like, doing the same type of work or different, where they sell their labor to their employer. They can also do both of these things at the same time, or do one and then the other as they choose to change jobs. There are also people who do not have these qualifications who do essentially the same work, but can ONLY sell their labor to their employer, and do not have the option of starting their own practice, therefore I would consider them specifically proletariat. Their wages are often very, very low, typically to the point of qualifying for different types of low income assistance programs.

I think this probably gets more complex, too, due to the fact that the work has been professionalized over time with the advent of the degree and the licensure requirements while non-professional workers are still widely used and exploited in tandem.

Or, would Social Workers and social service workers necessarily exist in different classes from one another due to the professionalization of one and not the other (in the eyes of the employer)?

So yeah I'd love to hear any thoughts on this

This is somewhat long, and somewhat cringe. The short version is that I think Marx had really interesting things to say about religion, and I think materialist theory of religion should form a part of any socialist project, because it's the reality from which we are working with. Even if most of us are atheists, we have to have a working theory of religion and an understanding of religious people, because they will necessarily be part of any revolution that occurs.

...

Marx's views on religion are expressed throughout his work, most eloquently in the introduction where he wrote his famous opium of the people line. This resonates with me, not as some epic takedown of religion, but for its refutation of the mechanical-materialist atheism of Feuerbach, which in some sense echoes in modern New Atheism. Marx, despite his atheism and materialist philosophy, found humanistic compassion for the followers of religion, by applying his materialism to religion. From this he identifies an indispensable function of religion: it soothes the pain of alienation and exploitation inherent in class society. So, his proposal for abolishing religion is not to ban religion, but to abolish the material conditions which require religion; i.e., abolish class society, which today is predicated on private property and wage labor.

This is as good an expression of my feeling toward religion as I have found. Yet, it still feels... incomplete? It feels like there is more to say on this topic, but for Marx it seems that he is content to believe that, like the state, religion will wither away with class society.

There are two questions that I return to:

- Could religion really disappear with the abolition of class society?

- Could a secular institution replace organized religion (the church, e.g.)?

Here is where some speculative, maybe half-baked thinking begins…

I wish Marx took what he said above just a step further. I would modify it to say that the abolition of class society would not abolish religion as such, but only the form of religion required by class society.

The basis of religion is suffering. This is why it has to act as opium. Class society has been the most terrible source of suffering, exploitation, and alienation for the past several millennia, as class society in various forms has expanded with the growth of civilization. Yet humans have practiced religion for as long as humankind has existed, even in those primitive communal societies analyzed by Marx and Engels.

In chapter 7 of Capital Volume I, Marx connects production and abstract thought:

A spider conducts operations that resemble those of a weaver, and a bee puts to shame many an architect in the construction of her cells. But what distinguishes the worst architect from the best of bees is this, that the architect raises his structure in imagination before he erects it in reality. At the end of every labour-process, we get a result that already existed in the imagination of the labourer at its commencement.

In other words, (1) abstract thought is a prerequisite for human labor, (2) as part of the labor process, the mind conjures up an ideal, perfected versions of concrete objects. This acts not only on external things, but is directed at ourselves too: we produce things in order to perfect our appearance, health, education, or innumerable other attributes. So as a prerequisite, in order to produce as humans, as a practical fact we already imagine ideal versions of ourselves which we want to bring to reality. And if there are barriers to the realization of this ideal, that elicits suffering.

When humans feel they lack the power to shape reality to their ideal, this can happen for one of two reasons. Either it is controlled by nature, such as the weather, in which case religious practice is oriented toward nature; or it is actually controlled by humans, but they are not aware or capable of using that control. This second reason is alienation, and it is the type of religion seen in most of the capitalist world today. Just as we alienate our political power from ourselves and place it in secular institutions of government, so also we (or at least, the religious) alienate themselves from moral power and place it onto an idealized version of themselves (god, jesus, whichever) which has the ability to judge and forgive. But this alienated spiritual existence only mirrors the actual alienation experienced in our social existence.

If it is the case that class society produces a form of religion, not religion as such, then the answer to (1) is: no, the disappearance of class society will not end religion. Religion will only change form, in a way that addresses the forms of suffering experienced by people in a post-class world. Therefore the answer to (2) is straightforwardly: maybe, if a socialist society can come up with a rational institution which is capable of really addressing the suffering experienced by all the individuals in society. But I would bet against the idea that we will actually achieve utopia.

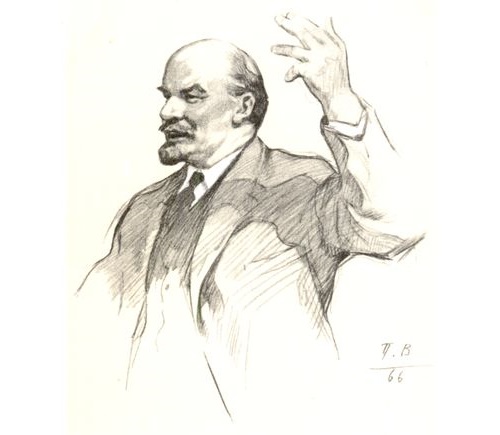

(Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov; Simbirsk, 1870 - Nijni-Novgorod, 1924) born on april 22 was a Russian communist leader who led the October Revolution and created the Soviet communist union. A member of a middle-class family in the Volga region, his animosity against the tsarist regime was exacerbated after the execution of his brother in 1887, accused of conspiracy. He studied at the Universities of Kazan and Saint Petersburg, where he settled as a lawyer in 1893.

His activities against the tsarist autocracy led him to come into contact with the main Russian revolutionary leader of the time, Georgy Plekhanov, in his exile from Switzerland (1895); it was he who convinced him of the Marxist ideology. Under his influence, he helped found in Saint Petersburg the League of Combat for the Liberation of the Working Class, the embryo of the Russian Social Democratic Labor Party chaired by Plekhanov.

In 1897, Lenin was arrested and deported to Siberia, where he devoted himself to the systematic study of the works of Marx and Engels. After his liberation in 1900 he went into exile and founded the newspaper Iskra (the spark) in Geneva, in collaboration with Plekhanov

In the II Congress of the Russian Social Democratic Party (1903), Lenin imposed those ideas at the head of the radical Bolshevik group, which defended his strongly disciplined party model as the vanguard of a revolution that he believed was viable in the short term; In 1912, the break with the Plekhanov and Martov Menshevik minority would be definitively confirmed, attached to a mass party model that would prepare the conditions for the triumph of the workers' revolution in the longer term.

In 1905 Lenin returned to Saint Petersburg to participate in the revolution that had broken out in Russia, Lenin considered that movement as a "dress rehearsal" of the socialist revolution, of which he especially appreciated the spontaneous organizational form of the Russian revolutionaries, such as the soviets or popular councils. he would go into exile again in 1907 due to the failure of the revolution.

Lenin was completing a revolutionary program of immediate application for Russia: mixing the heritage of Marxism with the insurrectionary tradition of Louis Auguste Blanqui, he proposed to anticipate the revolution in Russia by being this one. from the "weak links" of the capitalist chain, where a small group of determined and well-organized revolutionaries could drag the working and peasant masses into a revolution, from which a socialist state would emerge.

The outbreak of the First World War (1914-18) gave him the opportunity to put his ideas into practice: he defined the conflict as the result of the contradictions of capitalism and imperialism and, in the name of proletarian internationalism, later, the deterioration of the tsarist regime as a result of the war allowed him to think about launching the socialist revolution in his country as the first step towards an era of world revolution.

The Russian Revolution

When the February Revolution of 1917 overthrew Tsar Nicholas II and brought Kerensky to power, Lenin rushed back to Russia with the help of the German army (which saw in Lenin an agitator capable of weakening his enemy Russia). He published his April Theses ordering the Bolsheviks to cease support for the provisional government and to prepare their own revolution by claiming "all power to the Soviets."

A first failed attempt in July forced him to take refuge in Finland, leaving Trotsky to lead the party to seize power through a coup in early November 1917 . The coup became the triumphant October Revolution thanks to the Bolshevik strategy of focusing their demands on the end of the war and the distribution of land . Lenin immediately returned to preside over the new government or Council of People's Commissars.

As the leader of the Bolshevik Party , he has since directed the building of the first socialist state in history. He fulfilled his initial promises by removing Russia from the war for the Peace of Brest-Litowsk (1918) and distributing expropriated land to peasants from large landowners.

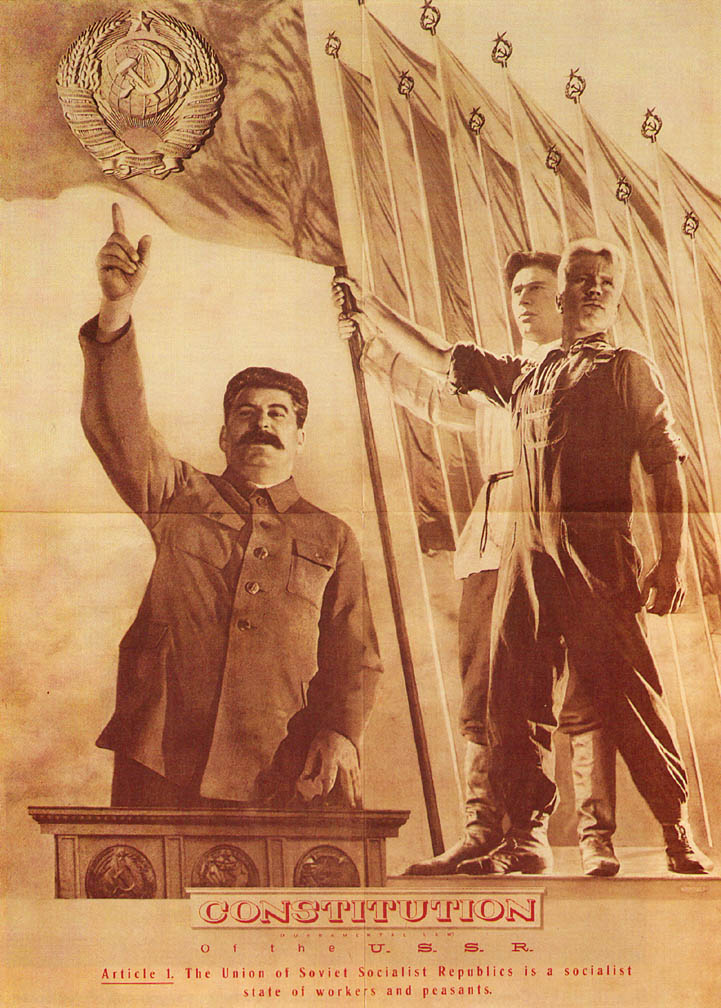

He delegated to Trotsky the organization of the Red Army, with which he managed to resist the combined attack of the white armies and foreign intervention in the course of a long Civil War (1918-20). Once control of the old empire of the czars was recovered, he articulated the territory by creating the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (1922), which he gave a formal organization by the Constitution of 1923.

Driven by the needs of the war, but also following his own ideological convictions, he imposed a policy of immediate socialization of the economy, nationalizing the main means of production and subjecting activities to strict central planning (war communism); the difficulties of such a radical transformation caused the collapse of production and a general disorganization of the Russian economy.

Lenin then had to rectify his initial mistakes, convincing his party of the need to introduce the New Economic Policy (1921), which consisted of going back on the path of socialization, leaving a certain margin for freedom of movement. market and private initiative (authorization of foreign investments, freedom of wages), with which it achieved an appreciable economic recovery.

Plagued by a serious illness, Lenin gradually retired from the political leadership, while he saw how his collaborators - especially Trotsky and Stalin - began the dispute over the succession. he eventually passed away in 1924

Lenin is known for establishing the political tradition of Marxism-Leninism, which emphasizes the creation of a dictatorship of the proletariat by means of a revolutionary vanguard party and democratic centralism, in which political decisions reached through free discussion are binding upon all members of the political party.

Lenin is one of the most influential political thinkers of modern history, authoring influential communist texts such as "Imperialism, the Highest Stage of Capitalism", "State and Revolution", and "What Is to Be Done? Burning Questions of Our Movement".

-

What is to be Done

In which he defended the possibility of making a socialist revolution triumph in Russia as long as it was led by a vanguard of determined professional revolutionaries organized like an army.

In which he defended the possibility of making a socialist revolution triumph in Russia as long as it was led by a vanguard of determined professional revolutionaries organized like an army. -

Imperialism, the Highest Stage of Capitalism:patrick-lenin: he defined the conflict (world war 1) as the result of the contradictions of capitalism and imperialism

-

The State and Revolution :lenin-fancy: Lenin defined this state as a transitory and necessary phase of the dictatorship of the proletariat, which was to prepare the way for the communist future.

-

Lenin's speech: The Middle Peasants ☭ Ленин: О крестьянах-середняках :lenin-cat:

-

Lenin's speech:What Is Soviet Power? / Ленин:Что такое Советская власть?

-

Lenin in October

is a 1937 Soviet biographical drama film -

🐻Link to all Hexbear comms https://hexbear.net/post/1403966

-

📀 Come listen to music and Watch movies with your fellow Hexbears nerd, in Cy.tube](https://live.hexbear.net/c/movies

-

🔥 Read and talk about a current topics in the News Megathread https://hexbear.net/post/4648058

-

⚔ Come talk in the New Weekly PoC thread https://hexbear.net/post/4652037

-

✨ Talk with fellow Trans comrades in the New Weekly Trans thread https://hexbear.net/post/4647580

-

👊 New Weekly Improvement thread https://hexbear.net/post/4641452

-

🧡 Disabled comm megathread https://hexbear.net/post/4592894

-

Parenting Chat https://hexbear.net/post/4638864

reminders:

- 💚 You nerds can join specific comms to see posts about all sorts of topics

- 💙 Hexbear’s algorithm prioritizes comments over upbears

- 💜 Sorting by new you nerd

- 🌈 If you ever want to make your own megathread, you can reserve a spot here nerd

- 🐶 Join the unofficial Hexbear-adjacent Mastodon instance toots.matapacos.dog

Links To Resources (Aid and Theory):

Aid:

Theory:

Talking more about how we in the imperial core are exploited, rather than how imperialism exploits other countries' resources, labour etc. I'm trying to find a satisfying explanation for why "well-paid" workers are also exploited.

From my understanding of Marx, exploitation happens in capitalism by the worker producing more value than what they are paid. This is evident by the profit these companies make, as it wouldn't exist if their workers were not exploited. But I find it awkward to try to get this across to people not well versed in theory. You have job types like office workers that don't really produce anything and only contribute to the companies bottom line indirectly. I get that theres unproductive and productive labor, but this is also alot to explain to someone who is not deep into economics.

This also got me thinking that exploitation is broader than just underpaying workers. There's also psychological and physical abuse at the workplace that I feel has some connection to exploitation. The fact that the employer can threaten you with firing, or cutting some benefit also seems like exploitation to me.

The Progressive International is organizing the People's Academy:

Guided by the intellectual and practical work of socialist construction in the Global South, we are building a platform to enrich the debates, theories and strategies that underpin our common struggle for a better world.

The Academy, which is completely free, includes one online lecture (in English which will last about one hour) every two weeks plus a very extensive and comprehensive reading list. The reading list usually includes short texts or book chapters which are considered "mandatory" readings for the lecture, plus a list of more articles, longer texts, and books that are relevant to the material. The academy will start in April and continue until the end of the year. The first lecture is next Saturday, 5 April, at 15:00 UTC. Here you can find the reading list for the first week if you want to get a feeling of it.

I am not affiliated with the Progressive International, but I followed a "summer school" they organized last year, which was similar with this academy but shorter and it was a great learning experience. Especially for people who want to go more into theory and Marxism but are daunted by long texts, this could be quite useful. They also have set up a (non-mandatory) telegram groupchat where people can discuss the material and connect with comrades. I thought it would be a good idea to share in this space, to spread the word about it. Feel free to join if you want and share it around!

Talking about striking workers:

“It is in truth no trifle for a working man, who knows want from experience, to face it with his wife and children, to endure hunger and wretchedness for months together, and to stand firm and unshaken through it all. What is death, what the galleys which await the French revolutionist, in comparison with gradual starvation, with the daily sight of a starving family, with the certainty of future revenge on the part of the bourgeoisie, all of which the English working man chooses in preference to subjection under the yoke of the property-holding class... people who endure so much to bend one single bourgeois will be able to break the power of the whole bourgeoisie.”

spoiler

Let’s revive the Marxism sub comrades

Italian intellectual and political activist, founder of the Communist Party (Ales, Sardinia, 1891 - Rome, 1937). Thanks to the support of his brother and his intellectual capacity he overcame the difficulties produced by his physical deformity (he was hunchbacked) and by the poverty of his family (since his father was imprisoned, accused of embezzlement). He studied at the University of Turin, where he was influenced intellectually by Benedetto Croce and the socialists.

In 1913 he joined the Italian Socialist Party, immediately becoming a leader of its left wing. After working on various party periodicals, he founded, together with Palmiro Togliatti and Umberto Elia Terracini, the magazine Ordine nuovo (1919). Faced with the dilemma posed to socialists around the world by the course taken by the Russian Revolution, Antonio Gramsci chose to adhere to the communist line and, at the Livorno Congress (1921), split with the group that founded the Italian Communist Party.

Gramsci belonged from the beginning to the Central Committee of the new party, which he also represented in Moscow within the Third International (1922); he endowed the formation with an official press organ (L'Unità, 1924) and represented it as a deputy (1924). He was a member of the Executive of the Communist International, whose Bolshevik orthodoxy he defended in Italy by expelling from the party the ultra-left group of Amadeo Bordiga, which he accused of following Trotsky's line (1926).

He soon had to go underground, since since 1922 Italy was under the power of Mussolini, who would exercise from 1925 an iron fascist dictatorship. Gramsci was arrested in 1926 and spent the rest of his life in prison, subjected to humiliation and ill-treatment, which added to his tuberculosis to make prison life extremely difficult, until he died of cerebral congestion.

In these conditions, however, Gramsci was able to produce a great written work (the voluminous Prison Notebooks), containing an original revision of Marx's thought, in a historicist sense and tending to modernize the legacy of Marxism to adapt it to the conditions of Italy and twentieth-century Europe. Already at the Lyon Congress (1926) he had advocated the broadening of the social bases of communism by opening it to all classes of workers, including intellectuals. His theoretical contributions would powerfully influence the adaptation of Western communism that took place in the sixties and seventies, the so-called Eurocommunism. 🤮

Gramsci’s concept of hegemony. Gramsci saw the ruling class maintaining its power over society in two ways –

Coercion – it uses the army, police, prison and courts to force other classes to accept its rule

Consent (hegemony) – it uses ideas and values to persuade the subordinate classes that its rule is legitimate

Hegemony and Revolution

In advanced Capitalist societies, the ruling class rely heavily on consent to maintain their rule. Gramsci agrees with Marx that they are able to maintain consent because they control institutions such as religion, the media and the education system. However, according to Gramsci, the hegemony of the ruling class is never complete, for two reasons:

The ruling class are a minority – and as such they need to make ideological compromises with the middle classes in order to maintain power The proletariat have dual consciousness. Their ideas are influenced not only by bourgeois ideology but also by the material conditions of their life – in short, they are aware of their exploitation and are capable or seeing through the dominant ideology.

Antonio Gramsci Marxists.org :gramsci-heh:

Antonio Gramsci and the Italian Revolution :anti-italian-action:

Hexbear links

- 🐻Link to all Hexbear comms

- 📀 Come listen to music and Watch movies with your fellow Hexbears nerd, in Cy.tube

- 🔥 Read and talk about a current topics in the News Megathread

- ⚔ Come talk in the New Weekly PoC thread

- ✨ Talk with fellow Trans comrades in the New Weekly Trans thread

- 👊 Share your gains and goals with your comrades in the New Weekly Improvement thread

- 🧡 Disabled comm megathread

reminders:

- 💚 You nerds can join specific comms to see posts about all sorts of topics

- 💙 Hexbear’s algorithm prioritizes comments over upbears

- 💜 Sorting by new you nerd

- 🌈 If you ever want to make your own megathread, you can reserve a spot here nerd

- 🐶 Join the unofficial Hexbear-adjacent Mastodon instance toots.matapacos.dog

Links To Resources (Aid and Theory):

Aid:

Theory:

I always see entropy used here and there in decriptions/critiques of capitalism, so I was wondering if there are papers or books that dive deeper on the topic. Thanks!

cross-posted from: https://hexbear.net/post/64349

The Soviet monetary system stood the test of war. Thus, the money supply in Germany during the war years increased 6 times (although the Germans brought goods from all over Europe and a large part of the USSR); in Italy - 10 times; in Japan - 11 times. In the USSR, the money supply during the war years increased only 3.8 times.

However, the Great Patriotic War gave rise to a number of negative phenomena that needed to be eliminated. Firstly, there is a mismatch between the amount of money and the needs of trade. There was a surplus of money. Secondly, several types of prices have appeared - rations, commercial and market. This undermined the importance of cash wages and cash incomes of collective farmers by workdays. Thirdly, large sums of money settled with speculators. Moreover, the difference in prices still gave them the opportunity to enrich themselves at the expense of the population. This undermined social justice in the country.

The state immediately after the end of the war held a series of measures aimed at strengthening the monetary system and increasing the welfare of the population. The purchasing demand of the population increased by increasing wage funds and reducing payments to the financial system. So, from August 1945, they began to abolish the military tax on workers and employees. The tax was finally abolished in early 1946. They did not conduct monetary and clothing lotteries anymore and reduced the size of the subscription for a new state loan. In the spring of 1946, savings banks began to pay workers and employees compensation for vacations not used during the war. The post-war restructuring of industry began. There was some growth in the commodity stock due to the restructuring of industry and due to a reduction in the consumption of the armed forces and the sale of trophies. To withdraw money from circulation, the deployment of commercial trade continued. In 1946, commercial trade gained a fairly wide scope: a wide network of shops and restaurants was created, the range of goods was expanded and their price was reduced. The end of the war led to a drop in prices on collective farm markets (by more than a third).

However, by the end of 1946, the negative phenomena were not completely eliminated. Therefore, the course on monetary reform has been maintained. In addition, the release of new money and the exchange of old money for new was necessary in order to eliminate the money that went abroad and improve the quality of banknotes.

According to the USSR People’s Commissar of Finance Arseny Zverev (who managed the finances of the USSR since 1938), Stalin first inquired about the possibility of monetary reform at the end of December 1942 and demanded that the first calculations be presented at the beginning of 1943. Initially, they planned to carry out the monetary reform in 1946. However, because of the famine caused by drought and crop failure in a number of Soviet regions, the start of the reform had to be postponed. Only on December 3, 1947 did the Politburo of the Central Committee of the All-Union Communist Party of Bolsheviks decide to abolish the card system and begin monetary reform.

The conditions for monetary reform were defined in the Decree of the Council of Ministers of the USSR and the Central Committee of the All-Union Communist Party of Bolsheviks of December 14, 1947. Money exchange was carried out throughout the Soviet Union from December 16 to 22, 1947, and in remote areas ended on December 29. When recalculating wages, money was exchanged so that wages remained unchanged. The change coin was not subject to exchange and remained in circulation at face value. For cash deposits with Sberbank, amounts up to 3 thousand rubles were also subject to a one-to-one exchange; on deposits from 3 to 10 thousand rubles, savings were reduced by one third of the amount; for deposits of more than 10 thousand rubles, two thirds of the amount were subject to withdrawal. Those citizens who kept large amounts of money at home could exchange at the rate of 1 new ruble to 10 old. Relatively favorable conditions for the exchange of cash accumulations were established for holders of bonds of state loans: bonds of a loan in 1947 were not subject to revaluation; bonds of mass loans were exchanged for bonds of a new loan in the ratio of 3: 1, bonds of a freely sold loan of 1938 were exchanged in the ratio of 5: 1. Funds that were in the settlement and current accounts of cooperative organizations and collective farms were revalued from the calculation of 5 old rubles to 4 new ones.

At the same time, the government abolished the card system (earlier than other victorious states), high prices in commercial trade and introduced uniform lower state retail prices for food and industrial goods. So, for bread and flour prices were reduced by an average of 12% against the current ration prices; for cereals and pasta - by 10%, etc.

Thus, the negative consequences of the war in the monetary system were eliminated in the USSR. This allowed us to switch to trading at uniform prices and reduce the money supply by more than three times (from 43.6 to 14 billion rubles). In general, the reform was successful.

In addition, the reform had a social aspect. Speculators pressed. This restored social justice, trampled during the years of war. At first glance, it seemed that everyone was hurt, because everyone had some money on hand on December 15th. But an ordinary worker and employee living on a salary, who by the middle of the month was no longer a lot of money, suffered only nominally. He didn’t even have money left, since on December 16 they began to issue salaries with new money for the first half of the month, which they usually did not. Salaries are usually paid monthly after the end of the month. Thanks to this extradition, workers were provided with new money at the beginning of the reform. The exchange of 3 thousand rubles of a 1: 1 deposit satisfied the vast majority of the population, since people did not have significant funds. Based on the entire adult population, the average contribution to the savings book could not be more than 200 rubles. It is clear that the “Stakhanovites”, inventors and other small groups of the population who had super-profits lost some of their money with speculators. But taking into account the general decline in prices, they, without winning, nevertheless did not suffer much. True, those who kept large amounts of money at home could be unhappy. This concerned speculative groups of the population and part of the population of the South Caucasus and Central Asia who did not know the war and for this reason had the opportunity to trade. who kept large amounts of money at home. This concerned speculative groups of the population and part of the population of the South Caucasus and Central Asia who did not know the war and for this reason had the opportunity to trade. who kept large amounts of money at home.

It should be noted that the Stalinist system was unique, which was able to withdraw most of the money from money circulation, and at the same time most ordinary people were not injured. At the same time, the whole world was struck by the fact that only two years after the end of the war and after a crop failure in 1946, the main food prices were kept at the ration level or even reduced. That is, almost all food was available to everyone in the USSR.

This was a surprise for the Western world and an offensive surprise. The capitalist system was literally driven into the mud by the ears. Thus, Great Britain, on the territory of which there was no war for four years and which suffered immeasurably less in the war than the USSR, could not cancel the card system in the early 1950s. At that time, miners went on strike in the former "workshop of the world," which demanded that they provide a standard of living like the miners of the USSR.

Cont. In the comments.

cross-posted from: https://hexbear.net/post/149520

One of the most large-scale projects of the world history - the so-called Great Plan of Nature Transformation, called "Stalin's Plan", because its development and approval at the legislative level (October 20, 1948) were initiated and personally controlled by I.V. Stalin [Bushinsky, p.9]. The plan was intended to solve several problems at once: the tasks of the immediate future were the rapid restoration of the national economy after the devastation caused by German Nazism; the next set of tasks covered the general improvement of the culture of land use in order to ensure the food security of the population in the long run; and finally the third set of tasks included the further evolution of large socio – technical systems through the acquisition of innovative technologies of environmental management, and therefore-a new civilizational leap of Soviet society.

SECTION 1: Background behind the creation of the Great plan for the transformation of nature

Direct material damage from the war and temporary occupation of part of the territory of the USSR by the enemy is estimated at 678 billion rubles (in pre-war prices), which is close to the total value of all Soviet investments for the first four five-year plans [Chuntulov, p.261].

Hitlerites and their accomplices completely or partially destroyed 1710 cities and over 70 thousand villages and villages, liquidated 31,850 enterprises, plundered 98 thousand collective farms, 1876 state farms, 2890 MTS, destroyed 65 thousand km of railways from 4100 railway stations, blew up 13 thousand bridges, caused other destruction. [Criminal goal..., sec. 310-311]

The plan for the post-war reconstruction of the national economy of the USSR provided for the allocation of 338.7 billion rubles to the economy in order to restore 3200 enterprises in the former occupied territories and build another 2700 new industrial facilities in other regions of the country [Chuntulov, p.262]. This breakthrough was to a large extent facilitated by monetary reform, the idea of which was born back in 1943–1944. [Zverev, p.231–232], however, the implementation immediately after the war turned out to be impossible, largely due to the consequences of the monstrous drought of 1946 [Spitsyn, p.17].

The drought zone of 1946-1947 occupied 5 million square kilometers (over 20% of the territory of the USSR) within the limits of the European part of the country at latitudes from 55° in the north to 35° in the south, which included Ukraine, Moldova, the Lower Volga region, the North Caucasus and the Central Black Earth region of the RSFSR [Koldanov, p.32; Spitsyn, p.17].

Because of the drought, the delivery of grain to the state only by collective farms of the Lower Volga region, for example, fell in comparison with 1945 by 21.7% in the Astrakhan region, 2 times in Saratov, 2.1 times in Stalingrad [Kuznetsova, p. 235]. In the first post-war years, the main production of legumes and many industrial crops was concentrated within the drought zone, as well as the largest industrial settlements with a high population, so the agrarian crisis was not only of local importance, but threatened to disrupt the plan for the restoration of the national economy and provoke a decline in the whole. The agricultural problem had to be solved against the background of the rapidly deteriorating international situation: as part of the policy of "containment of the USSR", according to the Truman Doctrine (March 12, 1947) - an American echo of the Fulton speech of W. Churchill (March 5, 1946) - the US government in March 1948 introduced export licenses that prohibited the export of most American goods to the Soviet Union [Katasonov, p. 32].

Under these conditions, Stalin returned to the project of integrated agroforestry in the steppe zone, the idea of which was first proposed in 1924 [korchemkina, p. 31]. For these purposes, it was planned to allocate 15 million rubles, but then the country, which was preparing for forced industrialization and had not yet completed collective farm construction, did not have the material resources or the human resources to implement such a large-scale task.

Forest plantations in the steppe and forest-steppe zones were carried out in Russia-the USSR long before 1948. but until the 19th century, it was mainly aimed at restoring the ship's and commercial forests. The practice of reforestation was established by Peter the Great in the 1720s, but until the 19th century it was mainly aimed at restoring the ship's and commercial forests. Exceptions to this rule are rare (e.g., protective forest plantations of the Don Cossacks on the Khopor River in the 18th century). [Mikhin]). The scientific substantiation of steppe afforestation for the purposes of protective, erosion control and reclamation purposes was an outstanding discovery of the Russian scientists of the XIX century - P.A. Kostychev, A.A. Izmailsky, V.B. Dokuchaev, N.G. Vysotsky, etc., who developed the system of dry agriculture [Logginov, p.5]. At the same time steppe forestries were created, the first of which was the Veliko-Anadolskoye (1843) in Yekaterinburg province [Yerusalimskiy, p.123].

A turning point in the history of steppe agroforestry is considered to be the period of Activity of V. V. Dokuchaev's Special expedition of the Voronezh province (1892-1898) in response to the drought of 1891, which covered 26 provinces and was accompanied by a terrible famine. During the expedition on the territory of the so-called Stone Steppe the system of protective forest plantations was created for the first time, an integral part of which were ponds [erusalimsky, p. 124]. As a result of the research, Dokuchayev proposed, among other things, a program of the following measures to regulate water management in the open steppes: (a) creation of pond systems in watershed steppe areas, the banks of which should be planted with trees; (b) planting of hedge rows; (c) continuous planting of forests in all areas inconvenient for arable land, "especially if they are open to strong winds" [Dokuchaev, p.104]. Similar conclusions were reached independently by climatologist A.I. Voyeikov, geologist V.A. Obruchev, chemist and economist D.I. Mendeleev [Kovda, p.16]. The latter in his “Explanatory Tariff” (1892) emphasized that “not only measures protecting forests from further reducing their proportion in all provinces where forests are less than 20% in area, but also stimulating intensified afforestation, are of particular state and direct agricultural importance. where the forest area is less than 10% of the entire surface ”[Mendeleev, p.306].

Like D.I. Mendeleev, many Russian scientists believed that growing forests in the steppe was a matter of national importance and, moreover, a manifestation of patriotism. In 1884, the forester M.K. Turskiy, having visited the Great Anadolu, said with fervent love: "You have to be there, on the spot, you have to see the Great Anadolu forest with your own eyes to understand all the greatness of the steppe afforestation, which is our pride. No words can describe the satisfying feeling that this forest oasis causes among the vast steppe on the visitor. It is indeed our pride, because in Western Europe you will not find anything like this" [quoted from: Koldanov,]

In Soviet times, the beginning of protective afforestation occurred in 1918, when the "Basic Law on Forests" was adopted (May 27), where the planting of forest crops was included in the number of planned reforestation measures. More detailed instructions are given by the Decree of the Council of Labor and Defense on combating drought (April 1921). The second period of steppe afforestation in the USSR is associated with the results of the All-Union Conference on Combating Drought (1931), where it was decided to plant 3 million hectares of forest mainly in the Volga region [Koldanov, p.23]. In total from 1931 to 1941. 844.5 thousand hectares of forest lands were laid, of which 465.2 thousand hectares fell on the share of field-protecting forest strips [Pisarenko, p.8]. The Great Patriotic War interrupted the development of steppe afforestation in the country. However, the drought of 1946 showed that in the experimental plots protected by forest belts, the grain yield is 3-4 times higher than on neighboring lands and reaches 6-17 centners per ha [Koldanov, p. 28; Prasolov, p.11]. The fight against drought by afforestation is one of the most important work vectors of the newly formed (in April 1947) USSR Ministry of Forestry [Koldanov, p.32]. In 1948, the third period began in the development of steppe afforestation in the Soviet Union, when, based on the teachings of Dokuchaev-Kostychev, a comprehensive 15-year project for agroforestry in the arid zone was created - the Great Stalinist Plan for the Transformation of Nature.

Continued in comments

cross-posted from: https://hexbear.net/post/213460

Propaganda artwork is titled <Felix Dzerzhinsky, 1877-1926. "Be Vigilant and Alert!" >

To correct the misunderstanding of what a political purge is - which is a result of the peopagandized education America feeds its citizens from cradle to grave - I am here to post excerpts of varying books from varying professional authors, historians, and journalists of varying political backgrounds on what "purging the party" actually entailed in the Soviet Union. If I run out of space in the main post, I will continue it in the comments.

_

The entire membership of the Communist Party was therefore subjected to what is called a “cleansing” or “purge” in the presence of large audiences of their non-Communist fellow workers. (This is the only connection in which the Soviet people use the term “purge.” Its application by Americans to all the Soviet treason trials and in general to Soviet criminal procedure is resented by the Soviet people.) Each Communist had to relate his life history and daily activities in the presence of people who were in a position to check them. It was a brutal experience for an unpopular president of a Moscow university to explain to an examining board in the presence of his students why he merited the nation’s trust. Or for a superintendent of the large plant to expose his life history and daily activities — even to his wife’s use of one of the factory automobiles for shopping — in the presence of the plants workers, any one of whom had the right to make remarks. This was done with every Communist throughout the country; it resulted in the expulsion of large numbers from the party, and in the arrest and trial of a few.

Strong, Anna L. The Soviets Expected It. New York, New York: The Dial press, 1941, p. 136

_

The purge–in Russian “chiska” (cleansing)–is a long-standing institution of the Russian Communist Party. The first one I encountered was in 1921, shortly after Lenin had introduced “NEP,” his new economic policy, which involved a temporary restoration of private trade and petty capitalism and caused much heart burning amongst his followers. In that purge nearly one-third of the total membership of the party was expelled or placed on probation. To the best of my recollection, the reasons then put forward for expulsion or probation were graft, greed, personal ambition, and “conduct unbecoming to communists,” which generally meant wine, women, and song.

Duranty, Walter. The Kremlin and the People. New York: Reynal & Hitchcock, 1941, p. 116

_

Kirov’s murder brought a change, but even so the Purge that was held that winter was at first not strikingly different from earlier Purges.

Duranty, Walter. The Kremlin and the People. New York: Reynal & Hitchcock, 1941, p. 116

_

The Central Committee organized a “purge” and expelled barely 170,000 members in order to improve the party quality. Stalin has frequently been held responsible for the “purge.” He was not its author. This party-cleansing was done under Lenin’s leadership. It is a process which is unique in the history of little parties. The Bolsheviks however, do not regard it as an extraordinary measure for use only in a time of crisis, but a normal feature of party procedure. It is the means of guaranteeing Bolshevik quality. To regard it as a desperate move on the part of leaders anxious to get rid of rivals is to misunderstand how profoundly the Bolshevik party differs from all others, even from the Communist Party’s of the rest of Europe.

Murphy, John Thomas. Stalin, London, John Lane, 1945, p. 144

_

Lenin initiated the first great “cleansing” of the Bolshevik party just as the transition had begun from “war communism” to the new economic policy. In 1922, when, as Lenin put it, “the party had rid itself of the rascals, bureaucrats, dishonest or waivering Communists, and of Mensheviks who have re-painted their facade but who remained Mensheviks at heart,” another Congress took place; and it was this Congress which advanced Stalin to the key position of Bolshevik power. It brought him into intimate contact with every functionary of the organization, enabling him to examine their work as well as their ideas.

Murphy, John Thomas. Stalin, London, John Lane, 1945, p. 145

_

The party maintains its quality by imposing a qualifying period before granting full membership, and by periodical ” cleanings” of those who fail to live up to the high standard set.

Murphy, John Thomas. Stalin, London, John Lane, 1945, p. 169

_

In all fairness I must add that no small proportion of the exiles were allowed to return home and resume their jobs after the Purge had ended.

Duranty, Walter. The Kremlin and the People. New York: Reynal & Hitchcock, 1941, p. 122

_

Besides examining Communists against whom definite complaints are made, the Control Commission at long intervals resorts to wholesale “purges” of the Party. In 1929 it was decided to institute such a purge, with a view to checking up on the rapid numerical growth of the Party, which has been increasing at the rate of about 200,000 a year during the last few years, and eliminating undesirable elements. It was estimated in advance that about 150,000 Communists, or 10 percent of the total membership (including the candidates) would be expelled during this process. In a purge every party member, regardless of whether any charges have been preferred against him or not, must appear before representatives of the Control Commission and satisfy them that he is a sound Communist in thought and action. In the factories non-party workers are sometimes called on to participate in the purge by offering judgment on the Communists and pointing out those who are shkurniki or people who look after their own skins, a familiar Russian characterization for careerists .

Chamberlin, William Henry. Soviet Russia. Boston: Little, Brown, 1930, p. 68

_

From time to time the party “cleans out” its membership, and this is always done an open meetings to which all workers of the given institution are invited. Each communist in the institution must give before this public an extended account of his life activities, submit to and answer all criticism, and prove before the assembled workers his fitness to remain in the “leading Party.” Members may be cleaned out not only as “hostile elements, double-dealers, violators of discipline, deganerates, career-seekers, self-seekers, morally degraded persons” but even for being merely “passive,” for having failed to keep learning and growing in knowledge and authority among the masses.

Strong, Anna Louise. This Soviet World. New York, N. Y: H. Holt and company, c1936, p. 31

_