this post was submitted on 30 Jul 2024

377 points (100.0% liked)

196

17619 readers

807 users here now

Be sure to follow the rule before you head out.

Rule: You must post before you leave.

Other rules

Behavior rules:

- No bigotry (transphobia, racism, etc…)

- No genocide denial

- No support for authoritarian behaviour (incl. Tankies)

- No namecalling

- Accounts from lemmygrad.ml, threads.net, or hexbear.net are held to higher standards

- Other things seen as cleary bad

Posting rules:

- No AI generated content (DALL-E etc…)

- No advertisements

- No gore / violence

- Mutual aid posts are not allowed

NSFW: NSFW content is permitted but it must be tagged and have content warnings. Anything that doesn't adhere to this will be removed. Content warnings should be added like: [penis], [explicit description of sex]. Non-sexualized breasts of any gender are not considered inappropriate and therefore do not need to be blurred/tagged.

If you have any questions, feel free to contact us on our matrix channel or email.

Other 196's:

founded 2 years ago

MODERATORS

you are viewing a single comment's thread

view the rest of the comments

view the rest of the comments

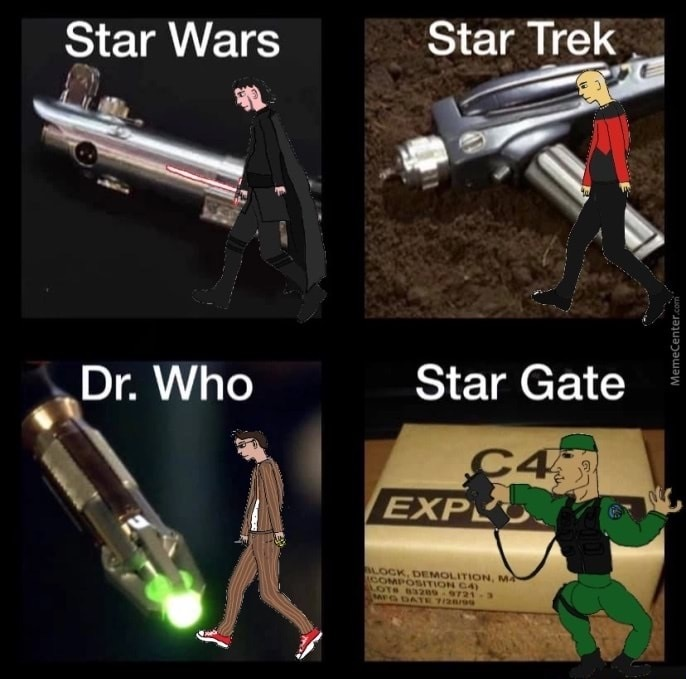

Star Wars just isn't sci-fi. Its technology should be treated the same way one treats magic in a fantasy story. Because that's what it is: a fantasy story. It's just space fantasy, rather than the more typical mediaeval or urban fantasy genres.

Sherlock Holmes is kinda meant to be that way. It's not the BBC version's fault, that's just faithful adaptation. Sherlock isn't meant to be a mystery series in the style of an Agatha Christie novel. It's more of a character study of a character so different from normal people. It's ok not to like Sherlock Holmes or adaptations of it (gods know...there's plenty of criticism out there for the BBC adaptation), but if you dislike it because it breaks Knox's rules of detective fiction, that's because you went into it with entirely the wrong expectations, rather than because it's poor storytelling.

To be fair, I've never read any of the original Arthur Conan Doyle novels so I'll take your word on it. I've heard that he famously hated the character of Sherlock Holmes and didn't understand why people found him so fascinating, to the point of trying to kill him off just so he could move on. So I can see the angle there.

But the thing about BBC Sherlock is, it's presented as a classic mystery story. They show Sherlock gathering clues, they give you some peeks into his thought process and what catches his attention, as if to say, "you should be paying attention too, this is potentially really important!"

Then later they go, "actually, the solution all hinges on this thing we just now revealed and that you couldn't have possibly predicted. Hope you enjoyed being taken for a ride, dipshit!"

And it's not really enjoyable to re-watch, knowing the solution and trying to spot the clues and foreshadowing; because in the end, what little foreshadowed there was adds up to fuck-all.

I'm on my Nth re-watch of House, which is really interesting by comparison because it was inspired by the same real-life person that was the inspiration for Sherlock. In spite of any other criticism that it deserves, I think it actually handles this aspect pretty well.

The viewer isn't supposed to actually understand the medicine, but the resolution of the case almost always leans on something that was mentioned by the patient, or just shown in passing, during the first act. Knowing the solution actually makes it more fun to re-watch, because you can spot exactly when this happens, and it's brilliant.

Wait really? I always thought it was just directly inspired by Sherlock Holmes himself.

I guess I was remembering something someone wrote on Reddit.

House has a ton of Sherlock Holmes references throughout, it was definitely the primary inspiration. But they also make a couple references to the surgeon Joseph Bell, the original inspiration for Sherlock.

Christie deliberately breaks Knox's rules, and for that matter, Willard Huntington Wright’s Twenty Rules usually seeing them as a challenge of how to include such features without alienating the reader. In some cases, for instance, the culprit is the maid or butler, but the character is well established before she is outed. In other cases, there are secret passages, or even affairs of state that might or might not figure into the mystery.

I'm not familiar with Wright's. I'll have to go look it up.

But yes, absolutely. I think that Knox's rules are actually even less rules and more guidelines than many other writing "rules", such as Chekhov's gun, are. And even those are only guidelines. Basically all of Knox's rules were specific examples of popular tropes at the time, where the real underlying issue was "don't make a mystery story where the solution is impossible to figure out even in hindsight by throwing in what is essential a deus ex machina".

Wright's pen name was S. S. Van Dine ( on Wikipedia ), a mystery writer himself when he posited his rules and (allegedly) obeyed them in his own stories.

Find the list here

Yeah thanks. I actually went and read his rules right after making my previous comment. My main thought was that it's basically a more explicit enumeration of the same underlying rules Knox had. Interesting to read, if only because it implies more about what his contemporaries were often doing wrong.