This makes it a one-cylinder motor, right?

If so, it’s a one-stroke motor. Kinda, sorta, maybe :P

How much squidpower we talkin' here

Only 8, one for each arm.

Nah. They need to push the gunpowder in from the "boom" side. We also count the "outs". Anchor into the cannon is a separate step and cannot just be hung on the outside.

Boom, gun powder in, stick out, anchor in, stick out.

5 strokes unless we count a "suck" for cooling the barrel.

Thoughts?

Now that I think of it (far more than a silly topic actually deserves), I’m convinced it’s a 2-stroke mechanism. Loading and firing are separate stages of the normal operation cycle. Think of that like the two stages of a power cycle of a 2-stroke engine.

Piston moving up is like cannonball and gunpowder going into the barrel in the loading stage. Gasoline igniting and moving the piston down is like gunpowder burning and propelling the ball out of the barrel.

Oh, that is good!

Yes, this is exactly as I thought!

In a typical 4-stroke engine, there is a process for resetting the engine between power strokes. The energy for the other three strokes (exhaust, intake, compression) comes from inertia in some sort of flywheel.

The "power stroke" in this system is not the gunpowder. It is the winching in of the cable.

In this system, the cannon is analogous to the flywheel: It merely resets the system between power strokes.

More specifically:

- Intake is the insertion of the powder and chain into the cannon

- compression is the firing of the chain.

- power, the stroke that powers the vehicle, is the pulling of the chain into the winch system.

- The exhaust phase is removing the chain from the winch system.

but how do you sail upwind?

So, wait, sailing is just horizontal flying?

Wait... I think you're right...? 🤯

I learned this when playing Valheim

Me too!!! Lol

Edit: I have been corrected. Please read the follow-up comments for better information. I'm leaving the original text below for context and transparency.

As I understand (I'll happily be corrected), the basic mechanism is that you want to align your ship diagonally off to the side, and the sails at a shallow angle so that the wind pushes you to the side (diagonally back and to the side, but the hydrodynamics of your bow resist the backwards component), so you gain some momentum. Then you turn into the wind to have that momentum carry you forward, sails parallel to the wind so it doesn't push you back as much. Turn off to the side again (either back to the same side, or continue your turn to the other side) and repeat.

It doesn't move you quickly, because it's rather inefficient in transferring the wind's power into opposite momentum, but it gets you moving at least a little.

Not sure if you're wrong or im misunderstanding what you are saying.

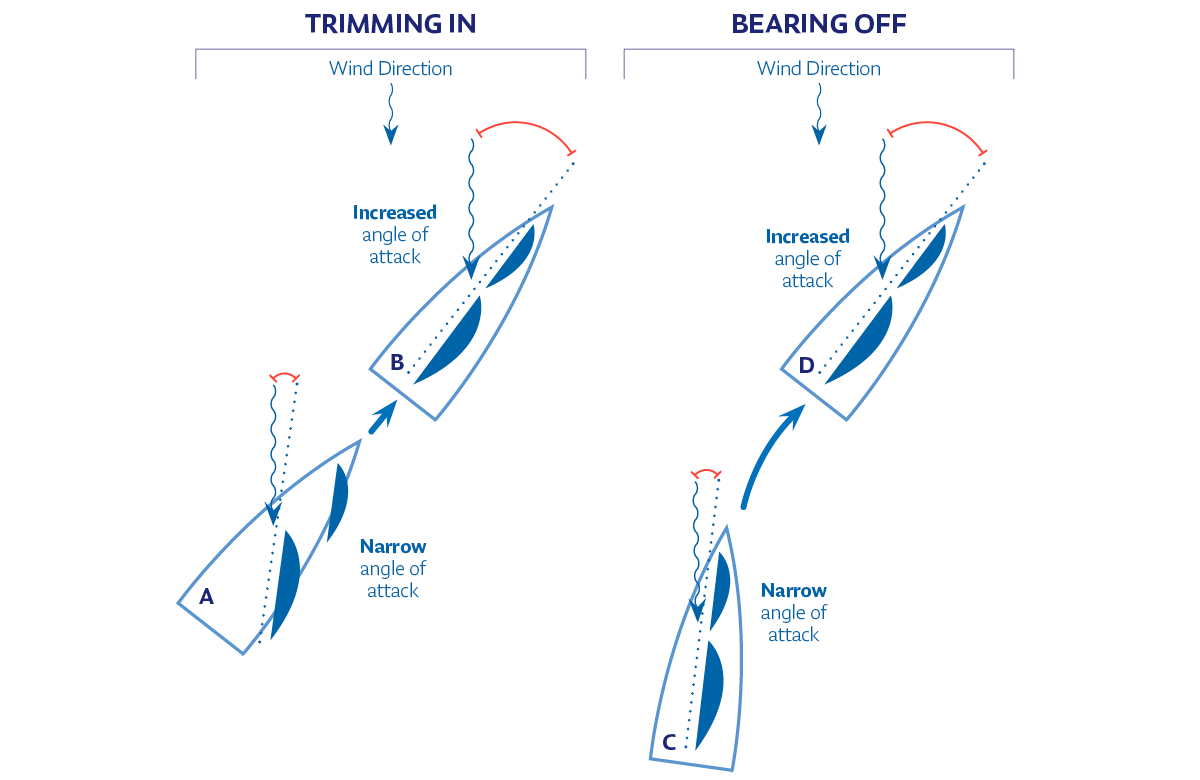

When sailing upwind think of sails as an aircraft wing with the top facing forward. As the wind passes over them from one side they generate "lift" at a perpendicular angle to the sail, pulling the boat in that direction, usually a combination of forward and sideways. The sideways is offset by your underwater profile, that resists sideways movement, resulting in (mostly) just the forward movement.

Square rigs like this comic often struggle sailing upwind compared to sloop rigs with two sails as the fore sail is used to generate that lift on the mail sail.

I've oversimplified this a lot so please not nit pick too much.

Sounds like I had it mostly wrong. I definitely didn't know about the wing / "lift" / pull mechanic. The only part I did get right was that the sideways component of the force is offset by your ship shape, and even that I misphrased.

Thanks for the correction!

All good, its much more than that but gives a general idea

A fun next lesson is the benefit of apparent wind. In addition to the wind relative to the water, you have added wind generated by the movement of the boat. Since the lift generated is related to the speed of the wind relative to the boat, the faster the boat goes, the more lift you get. As a result, it is possible to actually sail faster than the wind speed of the wind relative to the water.

I'm pretty sure I did a bad job explaining that. Google can explain it better for sure.

Similar thing - aparent wind shifts the wind direction forward. As such, how close a boat can sail to the wind decreases as the boat speeds up.

Not of the bow, but the center of all lateral resistance, which must be aft of the center of effort (sails). This includes the hull and rudder, but more important is the daggerboard/centerboard/keel, otherwise you would just be pushed downwind.

Keel was the word I was thinking of, but couldn't remember. Thanks for the correction!

And so Kedging is used only in tighter spaces where angles are not an option, like harbors or rivers

Also, while it doesn’t move you quickly, it still feels super fast due to the headwind adding to the feeling.

You don't sail directly upwind; sailboats can't do that. You sail at an angle to the wind.

EDIT:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tacking_%28sailing%29

Sails are limited in how close to the direction of the wind they can power a sailing craft. The area towards the wind defining those limits is called the "no-sail zone". To travel towards a destination that is within the no-sail zone, a craft must perform a series of zig-zag maneuvers in that direction, maintaining a course to the right or the left that allows the sail(s) to generate power. Each such course is a "tack". The act of transitioning from one tack to the other is called "tacking" or "coming about". Sailing on a series of courses that are close to the craft's windward limitation (close-hauled) is called "beating to windward".

Tacking

That's not even tack-y

xkcd

A community for a webcomic of romance, sarcasm, math, and language.